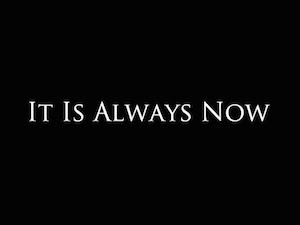

We are hurtling toward the Christmas holiday; Hanukkah began last night. But the sun is warming us in what feels like another extended summer. As my son grows, will he ever know the joy of a snowy winter morning? Humans everywhere are finding new and horrifying ways to harm each other, to spread fear. And all my four year old wants is to play with his new Land Rover and trailer from his Mom-Mom. Never have things seemed so simultaneously simple/beautiful and complicated/terrifying.

The world is swirling with minds trying to make sense of this confused new place. I feel friends leaning into each other a bit more urgently. I feel the anxiety tugging at us all. It reminds me of the tsunami of fear that washed over me exactly eight years ago, at the moment of my diagnosis, but this time, it feels universal, like we are all afraid of being washed away together, in some kind of mass erasure of our shared humanity. Paris, Colorado Spring, San Bernardino. Every day, everywhere. At least with my cancer, there was a contained root of evil. It was cut out, toxic drugs were pumped into my body. I was torn down, then reborn. But in this moment, how can we even identify the source of what threatens us? How can we possibly stem the tide if we don’t understand the seismic nature of what is erupting underneath?

This is not a place one can afford to dwell for any length of time. Not when there are children in our lives who need our constant steadiness and reassurance. Not when we are charged with the awesome responsibility of helping them grow and understand the mystery of everything around them. But last week – last week was filled with moments of real struggle. The evening ritual of listening to NPR while preparing dinner became untenable. Earl, so very attuned to everything around him (he really does listen to the news, some of the time), heard selected words about San Bernardino, and proclaimed, with a big smile, “California!” He knows it as the sunny place where we visited his cousins last winter, not the site of unspeakable carnage. Off went the radio. I immediately redirected our focus to play.

When my son was first born, I thought so much about wanting to shield him from the reality of my illness, about how it figures in my history, in the story of how he came to our family. But the fact is, my illness is a part of his story, for without it, he would not have come to us. So one day, perhaps not too long from now, the frightening legacy of cancer will be made real to him. It is an unsettling thing, to imagine opening up this part of the world to him, but it is known and understood, and we will handle it together, and grow as a family because of it.

Now, I think about wanting to shield him from a much larger reality, one that touches us all. I imagine the low-level anxiety that will creep in when we head to the airport to visit his grandparents in a few weeks. Every public place now holds some kind of threat, could be the sight of another mass murder. I do not want my son to grow up in a world where this is always true. This is unacceptable.

And yet, it is. It is accepted. A collective numbness has gripped us all. Chemo destroyed nerve-endings in my feet, left me with a lingering peripheral neuropathy. I can only hope that terror and violence haven’t similarly deadened our hearts and minds. We have to find another way. We must fight to stay awake.

Two weeks ago, I ran my second marathon, shaving over an hour off of my time from two years ago. Strong, steady weeks of training made it possible, along with the matter-of-fact belief of a new, incredible friend (who is not coincidentally, also a cancer survivor.) Running has become freedom for me, but completing a marathon is a special kind of insanity that is hard to explain to people who have never done it. Not unlike trying to articulate the feeling of being diagnosed with cancer to someone who has never had the experience. But now, in the calm after the race, now that my body has recovered and I can start imagining the next challenge, I understand more deeply what drives me in this way. The exhausted flush of BEING ALIVE that comes at the end of those 26.2 miles has so much meaning – after cancer, after Paris, after San Bernardino. After every single moment somewhere in the world where people want to bring each other – bring us all – to an end. And that life force is greater than any death that threatens us.

Stay alive, as big and as beautifully as you can. And one day, this madness will end.