As it turns out, there is much more to fear in life than the onset of a life-threatening illness. Fear of weakness, of facing limitations, of inadequacy, of conflict, of vulnerability – over the last five years, these manifestations of fear have all lurked around the psychic periphery since cancer tried and failed to fell me. These manifestations are perhaps less dramatic, but no less hindering, than fear of a life cut short.

When I began my post-cancer yoga practice almost two years ago, I never expected that one of its primary lessons would be about recognizing the on-going power of fear. After finishing treatment, once the long psychic hangover of chemo resolved, I joked that now that I’d faced cancer, there was really nothing left for me to fear. It’s a truism about cancer survival that my experiences with First Descents drove home, powerfully and repeatedly. As I rappelled off an enormous cliff in the Grand Tetons in the summer of 2009, the terror that gripped me was not of my ropes snapping and plummeting to a rocky death; it was reliving that which gripped me when I woke from surgery to the news of my cancer. And reliving that fear, with awareness, helped me to conquer it anew.

But the conquering of fear ultimately may be a practice, like yoga, rather than a finite act. Surviving my illness allowed me to pass through one kind of fear, leaving me in a place where its legacy is far more nebulous, but just as potent.

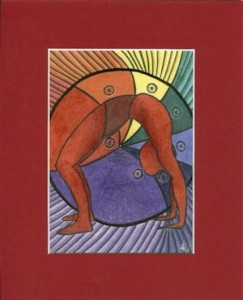

Last Monday, after weeks of procrastination, I finally reached out to my yoga teacher about my problematic relationship with wheel pose. It’s a pose that I’d easily attained in my life prior to cancer, when I practiced yoga sporadically and less seriously – when my body was much younger and leaner, before it was battered by surgeries and chemo. In my current body, though, wheel has become a mocking enemy of sorts – something totally counter to the spirit of yoga. With wheel, I’d erected an insurmountable barrier, and felt my inability to get there was symbolic of the fundamental damage that my cancer fight had done to me – and that for all of the rocks climbed and half marathons run, there was a way in which I would never be able to fully reclaim my body, or even all of myself, from this disease.

When I brought my frustrations to my teacher’s attention, and in the process shared the condensed version of my cancer story, she responded with characteristic openness and generosity, and sent me several long notes with ideas about how to approach the pose and where the issues might be in my body. During the course of the week, as her emails and ideas rolled in, I’d set myself up on the floor, and study what was going on with my body – were my hands flat on the ground? Where was I feeling constriction? Was I lifting too much with my arms and not enough with my legs? I’d assess, and then shoot off another note with my findings. Suddenly, the monster became approachable, as we worked on solving this puzzle together.

I headed to class last Friday morning excited, curious to see what I could do with all of this new information. Toward the end of class, after vigorous vinyasa work, my teacher, who customarily ends practice with a series of backbends culminating in wheel, shared with the entire class some of the tips and suggestions we’d been exchanging over email. She demonstrated the pose using blocks under her hands, and in my mind’s eye, things began to seem possible. She invited the entire class, filled with many people who have an established practice with wheel, to consider thinking about the pose in light of these suggestions.

I took my two blocks and pushed them against the wall. I lay on my back, and flipped my palms onto the blocks. Then, somehow, without the dread that had filled my mind and heart every other time I’d approached the pose, I extended my arms, and lifted my booty and my back off the ground, and found myself staring at the studio’s brick wall. How was this happening? My teacher approached. “That’s gorgeous, “ she told me. “You’re doing it.” Then it became real; I was up, in wheel. I felt myself begin to shake. “Come down when you’re ready,” she said.

I lowered myself to the ground. “You did it!” she said again. “How do you feel?”

The swelling in my chest rose to my throat, then my eyes, and tears ran quietly down my cheeks. “OK,” I said, gulping air, trying to contain a sob. I felt a hand on my shoulder. “That was amazing,” she said.

We moved into shavasana, and more tears came, as I suddenly felt myself back in the moment of my diagnosis. Outside the studio walls was the dark and chill of late fall, the time of year when cancer visited its wrath upon me. This momentous anniversary, five whole years, the fear I still hold in my heart, the worry that I won’t stay here for my son – all of it was loosed by this pose. I swallowed hard, and realized what had been unhooked when I lifted my heart to the sky. No wonder, then, that I had allowed wheel to feel so impossible for so long. My body knew something my mind did not, and was trying to protect me from that persistent hurt. So much of my survival has been about reclaiming and proving my strength, both physical and psychic. But part of survival is a pain that never leaves, but rather lingers, waiting for release.

These moments of surrender need not be feared.

Gah!!! Amazing, Emily. You, your observations, your writing. Everything. Love you!

Impressive story, Emily. I hope and wish for you that you can do the wheel pose for many, many years to come.

Best regards,

Theo