This one got blocked on YouTube as a result of copyright claim. I’m sure I’ll be dealing with more of that in the future.

Also, since video is completely optional, you can check out the commentary as a podcast on Apple, Spotify, or wherever else you like to listen to podcasts.

You can’t really talk rock guitar without a bow to Hendrix. This is a look at a smaller, less well-known song that still gives clear insight into much of what made Hendrix so special. His passion and emotion often mask the amount of planning and precision and economy he was able to summon. This little tune lets us see all of it in a very tidy package. Here’s the written edition of my Hendrix essay:

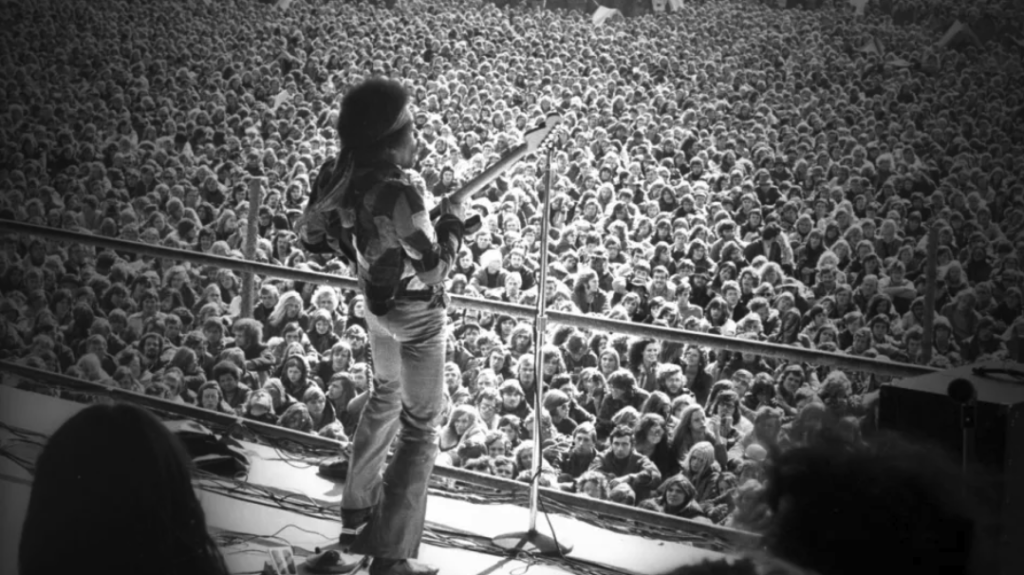

This came up the other day and it highlighted for me how we take Jimi Hendrix for granted. There is no way that I, born in 1972, can imagine the hysteria and the revolution that happened when this man was alive and making new music. And to make my ignorance worse, during my formative years I rebelled against Hendrix because he was “too popular.” In junior high and in high school I ended up spending a lot more time listening to the people Hendrix had influenced and the people he was influenced by. In a way, I’ve been only enjoying the bread and missing out on the best part of the sandwich.

Someone with more knowledge than I could do a whole season worth of podcasts on different aspects of Hendrix’s music and life, but for now I just want to focus on this one song and even just this one version of this song.

Now, this was a live version from an album called Hendrix in the West. The studio version can be heard on Both Sides of the Sky, which is a posthumous release. Hendrix’s catalog has victimized by disputes over his estate, so it’s a little hard for someone like me who only has a peripheral knowledge of the history, to know what version is “definitive.”

This live version, however, just jumped out of a shuffle and really got to me, so that’s the one I’m talking about. It’s from a show at Berkley on 5/30/1970 and it’s with Billy Cox on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums. This is the Cry of Love tour and the recording takes place about four months before Hendrix’s death. Based on YouTube videos from around the same time, Hendrix was regularly playing Love Man on this tour.

A lot of people think about Jimi’s epic (i.e. long) guitar solos, like Voodoo Chile and Machine Gun. We also tend to focus on the hits, like Hey Joe and Are You Experienced? But even in such an all-too-short career, Hendrix managed to cover a really diverse palette of music that was forward thinking, highly experimental, but also very organized and deliberate.

What makes Loverman worth talking about is that it is short at 3 minutes. It is structured somewhat like a twelve bar blues, but it has some easy decoration that makes it more of a rock or pop song rather than just a straight Blues interpretation. It has a great rock riff that anchors the song, but it also has a bridge at the end, which make it more of a narrative piece, rather than a blues that keeps going around the same progression. And this particular version has a few special moments that help highlight why I should have been listening to Hendrix from as soon as I could listen to music.

At three minutes, you might think there is not a lot to talk about, but when it comes to Hendrix, there are things that take literally two seconds that you can meditate over for hours and longer. It’s like what Talmudic study. And this it true all up and down the catalog, but there’s just a few things in this version of Lover Man that need mentioning.

The opening riff is the same as the studio version and has a classic Hendrix feel. That sequence takes seven seconds and then you are into the introductory Blues solo. It’s not a twelve bar, but just a one-four jam lasts about another six seconds. The solo (or fill, if you prefer) has a slow bluesy phrase, followed by some stinging right hand harmonics way up the neck and then darting back down to echo the opening riff right before the vocal starts. This is an example of how compact and efficient Hendrix’s play was. He could show you a Buddy Guy riff that was immediately followed by his disruptive technical innovations, and get right back to his blues all in the same phrase. That’s unequaled musical adroitness.

The verse has a twelve bar structure with Hendrix offhandedly doubling has vocal melody on guitar. There is no rhythm guitar, but the doubled notes (voice and saturated guitar) fill the space while giving extra deference to the rhythm section, which you couldn’t get with a second guitar.

After a second verse which basically repeats the structure and feel of the first, we get the intro riff again to prep for the solo. And what a solo. I think it’s much harder to really light up a solo in such a short space. There is no runway. Of course, to Hendrix this not a problem. Here we get the innovation of pedal effects that enhance the already distorted guitar without obscuring tone. As the extra distortion and sustain announce themselves, Hendrix slows way down – not to make silence, but to give the bends and sustain a chance to show themselves. Then we get the Octavia and more right hand harmonics to give us almost a San Francisco psychedelic amble. At the end of the first 12 bar cycle of the solo, Hendrix hits the Blues hard, very familiar turf to set up the very unfamiliar trick he’s about to attempt.

For the second part time through, Hendrix starts playing a grisly version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee. Although its a fairly ubiquitous piece of Classical music, it’s still Classical music! And yes this is a gimmick rehearsed with its own bass part and appearing similarly on other live recordings from this tour. But think about what this stands for. Hendrix is the Walt Whitman of rock guitar here – he contains multitudes. He hears all the music at the same time, it seems .- ALL the music. What’s so extraordinary and so hard to understand is that he could pretty much play it all at the same time too. I don’t want to dwell too much on the gimmick, but I think as we consider Hendrix’s legacy, this is inescapable proof that he was listening to and playing Classical music, even if its meant to be tongue in cheek.

After the stunt, we get a classic Hendrix innovation where he puts his stamp on the blues by going back to his I-IV jam (or I-IV-VII-IV), but this time for a vocal refrain instead of a guitar solo. This is Jimi inventing new music, creating a space for rock music that is based on existing forms, but still totally new and unique.

After this vocal jam there are some closing hits and a walk down, but they are merely transitions to Jimi doing his very special solo guitar trick, and by solo, I mean no bass and no drums. Just Jimi, Star Spangled Banner style. There are a lot of these moments, even in his too small recorded legacy. I don’t know if this type of expression grew out of Jimi’s competition with The Who to see who could get crazier at the end of songs, or what. I can, however, say with certainty that this is a trick that Jimi really enjoys and was really good at. It sounds like he can completely lose himself in these moments, almost like taking a victory lap to celebrate the end of the song. A lot of people have messed around with this paradigm. Stevie Ray gets pretty close. Neil Young did a whole album of these feedback endings,. But no one ever did it like Jimi. And the could do these several times per night, but they don’t get old or repetitive.

Whatever these solo bits are, and however you want to describe them, they are sonically astonishing. And the one that closes this version of Lover Man is no exception. Though modest in size, it has all the elements: Whammy bar, riffs to die for, just the right effects.

And that’s it. All that in jut three minutes of music. And the last thing you hear is Jimi tuning up to deploy the next masterpiece on his appreciative audience.