John Lee Hooker managed to be broadly popular but also enigmatic and inimitable. On this episode of the Escape Pod I look at a tremendous track from 1971’s Hooker ‘n’ Heat to understand what made John Lee so special and why his influence will never leave us.

As always, I’m talking all over the music and only playing snippets. That’s not how you experience music! So, after you listen to the podcast (or maybe even before), here is the playlist for music featured in the episode:

Boom Boom Boom – John Lee Hooker (1961): https://youtu.be/2SxSa6a6am4

One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer – George Thorogood (1977): https://youtu.be/sDf0IwXoOmY

Wild About You Baby – Hound Dog Taylor (1973): https://youtu.be/DdXdsyDJC5Y

Boom, Boom, Boom (Blues Brothers movie) – John Lee Hooker (1980): https://youtu.be/nUUyFrHERpU

Bad Like Jessie James – John Lee Hooker (1966): https://youtu.be/zsd_jwLWrDc

Burnin Hell – John Lee Hooker (1971): https://youtu.be/mZD2eQE2yp4

Hello and welcome back to the MPOMY Escape Pod podcast. Today we are getting out the official Escape Pod magnifying glass to look ever-so-closely at just a few minutes of the genius of John Lee Hooker. It’s the 1970 recording of ‘Burnin’ Hell’ on the 1971 release Hooker ’n’ Heat with Canned Heat. It’s a great record all the way through, but we’re just going to get hyper-focused on this one track as a way to get into Hooker’s genius and connect some dots along the way. The Hook was such an extraordinary talent on vocals, on guitar, songwriting, the way he conducted his career – everything. AND he got to enjoy a lot of success in his lifetime, probably not as much as he deserved though. So, we’re getting into the Hook on this episode MPOMY Escape Pod podcast.

A few announcements first, I’m working on some playlists podcasts as a way to start talking about the role artificial intelligence in music listening (as opposed to production – which is probably more interesting, but that’s another podcast). I’m taking the shuffle and radio features of your favorite streaming services and potentially turning those into a way that we can live with technology by creating healthy relationships with AIs. There is a lot more research for me to do on this topic, but this new life form is here, so there is no time to waste.

The other piece of housekeeping is that another collaborative project is taking shape. It’s a literary conversation with societal implications and it’s also a game show / boxing match. More to come on that, but it should be pretty good and entertaining.

How did I come to John Lee Hooker? Very quickly, this goes back to high school, when I thought it would make me cooler than everybody else if I didn’t worship at the altar of Clapton, Page and Beck, but instead explored some of THEIR influences, which quickly brought me to Robert Johnson, Elmore James and John Lee Hooker. Of course, I had already heard a pretty good rendition of the John Lee Hooker boogie by none other than George Thorogood. I didn’t really have a problem with his 80’s take on the Blues, just like I didn’t have a problem with ZZ Top or the Fabulous Thunderbirds. Come to think of it, I was damn lucky to come of age as a music fan when blues was ascendent, a way for musicians to actually make money, sell records and have some financial success.

Now, you can get tired of George Thorogood’s recorded output pretty quick (whereas ZZ Top just keeps getting better and better the more you listen), but you have to give the Delaware Destroyer his due. [Because he paid his dues]. Before Thorogood sold millions with ‘Movin on Over’ and had hits with covers of Hooker’s compositions, he was acting as a roadie for Hound Dog Taylor in Chicago. Hound Dog Taylor is the reason Aligator Records came into existence and is a HUGE part of my personal Blues music education. He was a six-fingered slide player who sounded like Elmore James turned up to eleven. It was called ‘genuine house rocking music’ and there has never been a description so apt.

`https://www.youtube.com/embed/DdXdsyDJC5Y?start=31

The article where I learned about Thorogood being Hound Dog Taylor’s roadie nicely points out that Taylor was a strong presence in the 70’s Chicago Blues scene, and that included playing in the open air market on Maxwell Street.

Why is that place important for this particular story? Because it helps answer the question of how I got to John Lee Hooker. Now, I never had the Maxwell Street experience, but the movie “The Blues Brothers” features a scene in that very market with a rocking band playing the Blues. It’s a great scene that really shows off the place and the music, but you can tell it’s not quite authentic. For one thing, it’s not Hound Dog Taylor’s band playing, it’s a musician who has comparatively little connection to Chicago. More like Detroit and then California. It’s John Lee Hooker.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUUyFrHERpU]

The audio-only doesn’t do it justice. This is a feast for the eyes, with the band, the shops, the food and the people all making you want that Boogie so bad. If someone came up to me today and had never heard of John Lee Hooker and said, “I just have three minutes – Can I get an idea of what makes this artist so special?” I would show them that scene and they’d get it.

That’s pretty much what happened to me. The Blues Brothers is a movie that is light on plot but has one great musical performance after another. The scene with James Brown makes me cry, and getting to see Steve Cropper play in almost every musical number is a great treat. But when it came to that scene with John Lee, it literally felt like time had stopped and never wanted that Boogie to end.

Now let’s go back in time, back to Detroit where young John Lee Hooker is writing and recording under various names in order to not violate exclusivity clauses in his various record contracts. Somehow these shenanigans don’t get him in trouble, probably because the money is coming in fro everybody. Not tons, but with songs like Boom Boom Boom, Hooker is making a name for himself. Part of the appeal is that he is doing something no one has ever heard before – boogie. It let Hooker explore in any way that more strictly organized music would not have allowed. So, even if the song lacked repetition or predictability, it was anchored by his stomping foot and rhythmic guitar. The Bo Diddley beat is the closest thing I can think of for comparison, but it is so much more limited than Boogie. Hooker could write and re-write his songs while he was playing them, allowing the emotion of the moment to really take over. Songs, rather than a specific set of notes played over time, were more of a fluid accompaniment to that boogie beat where the story – the words – are expressed as part of the song’s organizing principal, rather than something that is separate from the music. Vocals and guitar can always vary depending on the need of the moment. For example, your could play up-tempo, like Boom Boom Boom, or something more like a salad – check out I’m Bad, Like Jessie James. Spontaneity is a way to access greater emotion. The same song is slightly different every time.

As you can imagine, this approach to music makes collaboration a littler tricky. The band has to be listening and anticipating. There has to be, on the part of professional studio musicians who don’t have a fraction of Hooker’s financial success, a decision about going against everything they’ve learned to be a success in their career. They are faced with the impossible question: “Are we going to try to fence him in or are we just going to go with it and see what happens?” Based on the recorded output, it was too often the former approach. Too often a producer or someone would be pushing the idea of having Hooker play more structured music. I think he even had some hits with this approach, and as much as Hooker was an innovator and a revolutionary, he definitely liked getting paid. So, there is clear evidence he was open to this idea.

When the Hook had his third great era of success, not coincidentally in the 1980’s, I think he perfected being able to meet in the middle. It doesn’t hurt that the person you are meeting is Carlos Santana. Starting in the 80’s Hooker was making these all-star records, with Santana, Bonnie Raitt, Van Morrison. These were big money sessions where you couldn’t just hope for the best and see what happened. The results are good though. Some of the material is Hooker singing over more structured songs and he doesn’t try to get up to any of his old tricks. In a few cases things are more wide open, but Hooker clearly has the confidence in the collaborators to make it work flawlessly, like it was all planned out, when you and I both know it was a tightrope walk.

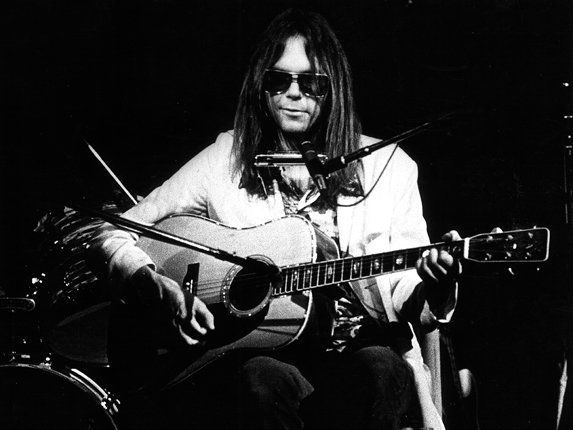

Those records are great, and the Detroit years are amazing, but the middle period, when John Lee went to join the hippies in California in the late 60’s, that’s a special moment in music and brings us back to the recording that is the subject of this essay.

BUT before we talk about this track, let’s just spend one minute on Canned Heat and, in particular, founder Alan ‘Blind Owl’ Wilson. This blue-eyed boy from Boston was so near-sighted that he earned the nickname from legendary guitarist John Fahey, who was also from Boston. Wilson’s contribution to the Blues is limited because he lived for such a short time, but all evidence points to Blind Owl being a very sincere Bluesman. He gets to San Francisco and starts Canned Heat, playing Hooker tunes and slightly reworked originals, in the classic style of Bluesmen throughout history. His knowledge runs deep, but the sound has a psychedelic tinge, almost like something to make up for Blind Owl being so awkward. Watch the Woodstock video – he’s unquestionably awkward. And that voice! How was that singing style ever considered OK?

[https://youtu.be/nBhpiUFSYWI?t=21]

It straight up doesn’t matter, because Woodstock made them popular enough to get a session with John Le Hooker in May of 1970.

Hooker ’n’ Heat is a double album where the first disc is classic John Lee Hooker, by himself (for the most part) playing guitar, singing and stomping his foot. He obviously is having a blast with Canned Heat, who are also producing the session. The next day, everyone takes up their electric instruments for some of that big boogie and the jams do not disappoint.

Canned Heat, and particularly Blind Owl understood Hooker’s foibles. This recording doesn’t sound like a dream team or a super session. On the contrary, this sounds like something that Wilson and Canned Heat had been getting ready to do for years in advance. Thy didn’t just KNOW ABOUT the Hook and his recording career. They GOT the Hook.

Which brings us to this tune – Burnin’ Hell. What a song! The lyrics are almost too much to get into, but it is intense! There are two characters, the singer and Deacon Jones. The singer is in some kind of a crisis of faith and is asking Deacon Jones to pray for him. Deacon Jones responds with the shocking statement that there is no heaven and that there is no hell. Ultimately, the Church offers NOTHING for the next life, but maybe there is comfort in this one. Hooker proceeds to stomp and howl with fear AND triumph. Death is a great mystery and no one, not the Church or anyone else, can say what happens after death, But one thing we can celebrate is that there is no Burnin Hell.

The song is amazing and Hooker’s performance at this session has all the things that make him perhaps the Blues GOAT – best singing, best guitar playing, best writing, best (uh…) arranging. But he is not alone in this performance.

For this one, he is joined by the Blind Owl on harmonica. Not on vocals, which I already mentioned, and not guitar, which was better, but also still a little quirky. Alan Wilson was a great Bluesman, but few would argue that he is one of the great all-time blues guitarists. For this track, he will just play harmonica and the result is transcendent.

But before the song even starts, there is some brilliant banter which is almost as important as the song itself. This stuff is priceless and we are so lucky to have access to this little conversation, and it is worth breaking down because a lot gets covered very quickly.

It starts with Hook saying that it doesn’t take him any time to make a record. Apparently he can just sit down and start cranking out tunes. There is even some joking that it should have been a triple (!) instead of double record. John Lee responds by saying that triple record would mean triple money. Canned Heat singer and (other) harmonica player Bob Hite tells Hook not to worry because it’s going to be a hit record (he was right!) and that money would just come rolling in. Then Hooker says that he has to worry about that money and utters the immortal phrase (a classic Hooker-ism) “Nothing but the best and later for the garbage. Natural facts.” Those are words to live by.

Next they talk about yet another harmonica player – the Grateful Dead’s Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. Hooker tells how his friend “Pig” lives on a farm with the pigs and the chickens. And that Pig says he’s a great cook, but his cooking is terrible, although his wife can cook. It’s brilliant to picture Hooker busting chops at Pigpen’s farm, and then later regaling Canned Heat with the story.

And then he mentions Blind Owl playing harmonica on the track they are about to record. He ADMITS that he doesn’t play any kind of “straight” Blues and says he doesn’t know how Wilson can follow him, but he somehow he can. And then the music starts. Here is that opening.

(Play up until the singing starts)

You know how I was saying before that if you only had a moment or two to learn about John Lee Hooker, you should check out that scene in The Blues Brothers. Well, this moment, which is only a little longer really gives you an even better insight, although it sadly lacks the all-important video content. But besides the Hook’s always dapper appearance, everything else is here, all the signatures rendered in unobstructed clarity. The beat of his stomping foot, probably mic’d separately. The sound of his hollow or semi-hollow body guitar, giving just a slight hint of feedback and acoustic-ness, but still very gritty and overdriven. It is a wonderful guitar tone.

But even more than the stomp and the guitar, even more than that Boogie that came as naturally to John Lee Hooker as did breathing, there is just a riveting vocal performance here. You can deconstruct and analyze these lyrics until they say and mean whatever you want. That exercise will end up telling you more about yourself than about the song or the singer.

But what’s actually in the lyrics is indisputably contradictory – a Deacon who says that there is no heaven and no burning hell. What kind of man of god is this? And how does the protagonist react? Is he happy that he’s not going to hell? Is he worried about the great unknown that lies beyond death?

It’s yes to all of the above. Fear and exhilaration and the infinite expanse of the unknown. You might say that’s pretty heady stuff for an old Blues song composed by a man who never learned to read or write. But then I would say that you haven’t listened to enough Blues music. If you think it’s not heavy, just listen to how the Hook belts this one out – “I DON’T BELIEVE…”

[https://youtu.be/JAZcGAKRiGs?t=201]

Adding to the legend and intensity of this particular track is the fact that it is the last recording Alan Wilson made. Before the record was finished, Wilson was found dead of a drug overdose. He was 27 years old. This ushered in a veery dark moment for popular music as, in quick succession, Wilson’s death was followed by those of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison.

Wilson may not enjoy the same reputation as those other three all these years later, but he had an innate sense for Blues music, a special understanding that couldn’t be learned in books or put on like a costume. As much as this recording of Burnin’ Hell is a contradiction of power and beauty, The Blind Owl was no archetypical Blues musician and he really didn’t look the part. But to John Lee Hooker, who I believe could see just fine, that didn’t matter one bit.

Thanks for tuning in to the MPOMY Escape Pod. As I mentioned, some literary discussion coming up and lots of other good stuff. Thanks for listening and we will see you next time in the Escape Pod.

The MPOMY Escape Pod podcast is an MPOMY Production, written by Michael Pomerantz.